Healthcare Features

- Details

- Written by: Sean Clement

- Category: Healthcare Features

- Hits: 748

The government's NHS reforms could have a significant impact on local authority estate asset management. Peter Hill looks at what is in store.

The White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS published in July 2010 set out a new vision for the NHS. The White Paper heralded great reform, proposing to change radically the nature of decision making for healthcare commissioning: turning it from top-down to bottom-up. The new National Health Service Act to implement the reforms is to pass through Parliament very soon.

Due for full implementation in 2013, the new bottom-up commissioning bodies for primary care will be General Practitioner (GP) consortia, with the remaining services to be commissioned by a new NHS Commissioning Board. Public health functions will pass to local authorities; PCTs and Strategic Health Authorities will disappear. Existing NHS Trusts will either achieve Foundation Trust status, or be re-organised by mergers so that all Trusts have Foundation status.

The developing market for health and community care

By the time the changes have been fully implemented, the split between commissioners of healthcare services and their providers will be complete. As this occurs, real competition should sharpen: there will be a much greater diversity of providers who may not be wedded to traditional ways of operating. In the coalition agreement, the government has signalled its expectation of much greater involvement of independent and third sector providers, and the aim of empowering every patient to choose any healthcare provider that meets NHS standards.

The changes will impact on estate asset management strategy: services may go mobile or be based around non-traditional locations. As care pathways are redesigned and cost pressures bite, the trend for moving services into the community will continue and remote working for health and social care professionals will proliferate. Cost savings from joint working and co-location will come to the fore. As the market develops and competition intensifies, both commissioners and providers will need better asset management skills to help deliver cost efficiencies and service improvements. Asset managers can expect a higher profile for what has traditionally been a low profile support service.

The detailed proposals for integration of PCTs with local authorities have yet to be announced, but it seems likely that ownership of the PCT estate will pass to local authorities. The process of integration of asset management functions will give rise to a number of issues: management structure and personnel for the combined asset management team, compatibility of databases and IT systems, alignment of budgets and agreement of a unified estate strategy and investment priorities. With pressure for cost savings so intense, rationalisation of the estate will be urgent.

It is clear that in future, achieving efficiency in asset management in the sense of good space utilisation and lowest lifecycle costs of an individual building, will not by itself be sufficient to achieve successful asset management. In future, asset management must also achieve success in effectiveness; that is to say, success in the contribution made by asset management to the organisation’s overall resource utilisation and performance standards in service delivery. The development of telecare services, new standards for patient accessibility, greater mobility in service delivery as well as recognised techniques for better space utilisation such as “hot desking” will affect the demand for, and type of accommodation needed.

For both the retained NHS estate and the PCT estate to be transferred to local authorities, there can also be little doubt that both organisational change and financial constraints will lead to a re-appraisal of what are truly core strategic assets, and a process of reshaping the estate over time.

Efficiency and cost savings – the whole local public sector estate

Transfer of PCTs’ public health functions to local authorities will mean that estate strategy decision making will be on a combined basis for all local authority service needs, including those for primary community care, but there is an even wider issue.

Opportunities for effective rationalisation of both the combined PCT and local authority estates will need to be considered in the context of the local public sector estate generally, and much greater emphasis will be placed on efficiencies achievable through joining up between local authorities and other public sector bodies. Through co-location of different public services where the relevant bodies are working jointly, rationalisation of the total local public sector estate offers the twin benefits of improved customer experience, and cost savings.

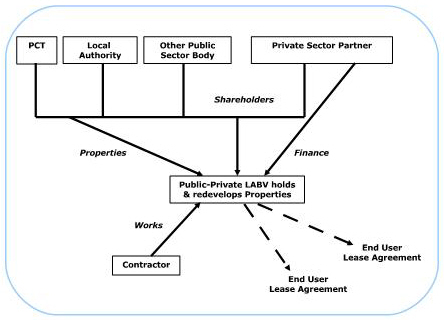

What asset management techniques would help to achieve these? A key issue is to find a suitable means for co-working public bodies to participate through a shared vehicle which can hold and redevelop property. If private sector capital is to be used, a Local Asset Backed Vehicle (LABV) may provide a solution (see Diagram). This is a form of public-private partnership which could be arranged to fit with e.g. a Local Enterprise Partnership.

The combined estates of a local authority and its PCT will contain a pool of assets which could be injected into an LABV, both properties ripe for redevelopment and income producing investments, which could provide security for finance to be raised by the LABV in order to carry out redevelopment. With an appropriate incentive for the private sector partner, the LABV could become a significant force for transformational change, delivering both rationalisation of the estate and a range of community benefits, reducing the local authority’s exposure to development risks and providing best value solutions.

The combined estates of a local authority and its PCT will contain a pool of assets which could be injected into an LABV, both properties ripe for redevelopment and income producing investments, which could provide security for finance to be raised by the LABV in order to carry out redevelopment. With an appropriate incentive for the private sector partner, the LABV could become a significant force for transformational change, delivering both rationalisation of the estate and a range of community benefits, reducing the local authority’s exposure to development risks and providing best value solutions.

Peter Hill is an Associate Director and Solicitor at TPP Law (www.tpplaw.com).

- Details

- Written by: Sean Clement

- Category: Healthcare Features

- Hits: 2968

The first groups of GPs who will take the lead in commissioning health services have been announced by Health Secretary Andrew Lansley.

The Department of Health has selected 52 groups of GP practices to become pathfinders for the new commissioning responsibilities proposed under the government’s NHS reforms.

The consortia, which involve 1,860 practices that provide care to 12.8m people in England, will test the arrangements before more formal structures are put in place.

They range in size from the Red House Group, which has three practices in Hertfordshire serving 18,900 people, to a consortium in County Durham that covers 90 practices and a population of 617,885.

They will manage local budgets and commission services for patients direct with other NHS bodies and local authorities.

The Department of Health said more GP consortia had come forward to join the pathfinder programme. A rolling programme of approvals will occur “over the coming weeks and months”, it added.

GP consortia will take on statutory responsibilities from April 2013.

Health Secretary Andrew Lansley said: “I am delighted by the response and the evident enthusiasm of the GP pathfinders for taking these ideas forward. They have shown that there are many GPs ready and willing to take on commissioning responsibilities, so they can make the decisions that better meet the needs of their local communities and improve outcomes for their patients.”

The pathfinders will receive support from the National Clinical Commissioning Network, the National Leadership Council and national primary care bodies, such as the Royal College of GP's Centre for Commissioning.

The government has also set up a Pathfinder Learning Network online hub to provide online support and resources.

- Details

- Written by: Sean Clement

- Category: Healthcare Features

- Hits: 957

The potential for “place-based budgeting” to deliver savings could be lost without a better understanding of the value of information and how it should be managed, a report for Socitm has claimed.

Socitm Insight conducted a study of the final reports into the 13 Total Place pilots. This found that “almost every one of them raise serious issues about information availability, quality, sharing and management”.

The report said problems with information exchange between public agencies centred on two main issues – the willingness to share and the format of the data.

“Getting a big picture of what is happening local is frequently prevented by fears, real or imagined, of transgressing the provisions of the Data Protection Act,” it said.

“Data formats can be equally problematic. Data may refer to different areas, or be aggregated at a level higher than the locality of interest. Double counting becomes an issue where there are different tiers of government. Finally, the sheer volumes of information involved present analytical and presentational problems.”

The Socitm report revealed inconsistency in approaches to data handling and exchange and the development of silos. One case study revealed that:

- Council A was able, through local negotiation to access to live birth data, housing benefit data and council tax benefit data.

- Council B worked with its local PCT to gain access to live birth data on a monthly basis

- Council C was unable to access any of this data with both the Primary Care Trust and the local authority’s legal team quoting the Data Protection Act as the barrier to access.

Report author Chris Head said: “If we are to protect the frontline despite the cuts, local, joined up, evidence-based approaches are essential. But these will not happen unless there is better understanding of what can be done now and what might be done in future to ease availability and collation of key datasets required to inform change.

“In addition, public services need to get their information assets in order and ensure that employees have essential skills in analysis, presentation and interpretation of data in order to deliver evidence-based decision-making.”

For more information, go to www.socitm.org.uk.

- Details

- Written by: Sean Clement

- Category: Healthcare Features

- Hits: 2204

Mark Johnson highlights the practical steps GPs and their partners should be taking to prepare for the new landscape of GP commissioning.

GP Commissioning may still be incubating but the world into which it will be born is already changing. The published timetable shows commissioning consortia formally taking over from Primary Care Trusts on 1 April 2013, but we are already seeing signs that system reforms are running ahead of the legislative timetable. PCTs have started winding down their operations, not replacing leavers from key posts and existing Practice Based Commissioning (PBC) groups are staking their claims to become GP Commissioning Consortia (GPCCs).

The draft Bill is expected shortly. While debate rumbles on about the speed and direction of system reforms, the fact remains that GPs have been presented with an historic opportunity to seize the initiative in shaping their local commissioning arrangements. Rather than waiting for the template that may never come, GPs should start preparing now on certain key areas as the timetable is very tight.

Governance and Leadership

Leaving aside questions about the optimum size of a GPCC, it is clear that there will be much work to do in garnering the necessary support from practices across a locality. All practices will need to be part of a GPCC, including those that up to now have chosen to go it alone. To prepare a cogent, cohesive plan, practices must start building a governance structure which allows a leadership team to be appointed, decision-making to be delegated and a level of legitimacy and trust built between the putative GPCC and its stakeholders.

From our work in helping to establish PBC groups as corporate entities, this process is likely to take up to two years to get right. It is not yet clear if GPCCs will be statutory public sector bodies or more akin to independent social enterprises. Whichever model ultimately prevails, there will be a lot of work to do in preparing a constitution, policies and procedures to allow the new GPCC to manage public funds, remain accountable to its stakeholders, demonstrate probity and avoid conflicts of interest (see below). Experience from developing PBC models also shows that GPs are more likely to engage if they can see the tangible benefits from participation and cooperation. These are not just financial incentives. They might also include training and development opportunities and new career pathways into leadership roles, as well as access to new equipment and technology. In our PBC models, a key document is the membership agreement between the practice and the consortium, which puts certain obligations on the practice and, ultimately, allows the consortium to expel them if they do not toe the line.

Managing the transition

The outline timetable shows GPCCs beginning to organise from April 2011. During 2012-13 they will operate in shadow form and receive their indicative ‘fair share’ budget allocations. They formally take over from PCTs on 1 April 2013. In practice, things are unlikely to be so neatly defined. The transition period during which PCTs wind up their operations has the potential to get very messy. GPCCs must give careful consideration to which parts of the PCT asset base, personnel and resources they take on. Careful due diligence is needed to avoid taking on onerous liabilities or unacceptable levels of risk. Particular danger areas will be inheriting PCT staff under a TUPE transfer and the transfer of assets and existing long-term contracts from the PCT.

The effect of TUPE Regulations may be to transfer the contracts of employment of PCT staff to the GPCC, whether they are needed or not. Also, any historic claims, pension entitlements and enhanced redundancy benefits could transfer too. In relation to assets and contracts, it is possible that PCTs will seek to transfer PFI contracts, ISTC contracts, onerous property leases and historic deficits. It is not yet clear whether there will be a national pot to deal with these, but they could present a significant risk in an already tight financial envelope for commissioning budgets.

All of this could add significantly to the GPCC’s cost base just when the government is seeking to reduce the management overhead to around one third of current PCT levels. To avoid this the GPCC must have a leadership team in place which can properly and robustly negotiate the terms of any transfer and properly consider risks could be mitigated by outsourcing functions to external providers.

Financial planning

Unlike GP fundholding, the commissioning budget will be held separately from practice budgets. Commissioning budgets will be based on the health needs of the locality using a “fair share funding” formula to be introduced from 2012 onwards.

If savings are made in commissioning activities, through improved care pathways, reduced prescribing and referrals, these have to be retained in the GPCC and reinvested in local services, not paid out to GPs. GPs’ reward for taking part in commissioning activities could therefore only come through (i) being a paid GPCC office holder (ii) the QIPP payment for improved outcomes or (iii) other membership benefits such as premises improvement or ICT upgrades.

Press reports have suggested that consortia will be paid a management fee of around £9-10 per patient per annum to discharge their commissioning responsibilities. If a minimum population size of around 100,000 is assumed, this will equate to a budget of around £1m per annum to run the organisation – about the same overhead as a well-run SME business. From this sum, the consortium must source premises, support services such as accounting, public health advice, data analysis, contracting and procurement. It seems obvious that the consortium will have to be a very lean operation. There simply won’t be any room for passengers and the leadership team will have to take look hard at how it can buy in only the essential services it needs to function. If sophisticated IT systems are needed to transform services and provide real-time data, it is unlikely that these can be set up and run internally from this kind of budget. Furthermore, it seems this budget only applies from steady-state operations as from 1 April 2013, so careful thought will be needed about how to manage the transition period.

The new goal for GPs and their commissioning consortia is to deliver a radically different health system, where GPs understand what is being spent and the outcomes being achieved; and crucially, it must cost less to run. Prospective consortia should begin preparing now, cast off pre-conceptions and keep an open mind on how to deliver this daunting challenge.

Mark Johnson is managing director of specialist law firm TPP Law and has advised a variety of PBC consortia and new provider organisations on their formation, governance and successful contract bids. A free report on preparing for GP commissioning is available at tinyurl.com/tpplaw.

Managing Conflicts of Interest

GP consortia will be exposed to conflicts of interest from many directions, including how they allocate budgets, award new service contracts and refer patients to provider companies.

How do they deal with these issues in a balanced and proportionate way, respecting their statutory duties and preserving public trust? Not by putting every new service out to tender, regardless of the economics, or to exclude clinicians entirely from decision-making on services. To do so means losing some benefits inherent in inclusive commissioning initiatives and pathway redesign. The solution lies in having a clear codified system for managing interest conflicts as part of the organisation’s process of governance.

What is a conflict of interest?

A conflict arises if (1) a person owes separate duties to act in the best interests of two or more bodies on the same or related matters, and those duties conflict, or there is a significant risk they may conflict (for example a board member of a consortium may also be an individual GP service provider); or (2) a person’s duty to act in the best interests of any patient or public body on a matter conflicts, or there is a significant risk that it may conflict, with his own interests in relation to that or a related matter.

Self-interest is not the only cause of conflicts. It could be a colleague or a family member has an interest in a particular situation, for example if a spouse was a GP holding shares in a provider company which stood to benefit from a new contract. A conflict can occur because an office holder owes duties to more than one organisation or board.

Regulating behaviour

The consortium constitution or terms of reference should detail the duty to act with integrity and maximum transparency. That normally requires that participants declare their interests – either in a written register or verbally in a meeting. These declarations should be updated regularly. Office holders should absent themselves from meetings or decisions where there is a material conflict of interest, unless their colleagues or rules of governance permit them to stay.

Boards should include independent non-executives to act as dispassionate guardians of public interest. Clinical professional rules are also key to regulating behaviour. The GMC’s Good Medical Practice provides clinical judgment guidance here.

Proportionate measures

Some believe all newly-commissioned services should go out to open tender to demonstrate compliance. This is disproportionate and likely to be costly. A key feature of the ‘any willing provider’ (AWP) model is that no guarantee of demand or activity levels is given. AWP is simply a licence to carry on the service should patients opt to use it. It is well-suited to services such as dermatology, cardiology or urology, where a nationally-agreed tariff exists and ‘choose and book’ applies. As such, there should be no significant financial benefit conferred upon the AWP participants, since they are subject to strict market disciplines.

Alternatively, if the consortium intends to provide significant guarantees of minimum activity levels and financial rewards, it is important to design and implement rigorous procurement procedures which ensure contracts are awarded fairly, without bias or self-interest. The process for contract award should be fully documented in advance. The criteria for award should be clear, objective and transparent.

This article first appeared in Primary Care Today (www.primarycaretoday.co.uk).